Juba, South Sudan — A network of shadowy companies and intermediaries is quietly capturing the lion’s share of South Sudanese crude exports, raising serious concerns about corruption, financial opacity, and the deterioration of state revenues. New documents and internal sources reveal that Cathay Petroleum, Euroamerica Energy, and a web of intermediaries have reactivated trading networks once associated with sanction-bypassing and high-risk practices.

Cathay Petroleum, a company founded in 2003 by a Chinese national operating between Hong Kong and Singapore, has surged from relative obscurity to become a major actor in South Sudan’s crude sector. Analysts describe its rapid rise as unusual, given its historic activity in sensitive markets such as Libya, Yemen, Sudan, and South Sudan, often through opaque structures and shell entities. The company’s sudden dominance mirrors patterns seen in trading networks historically linked to fraud and corruption.

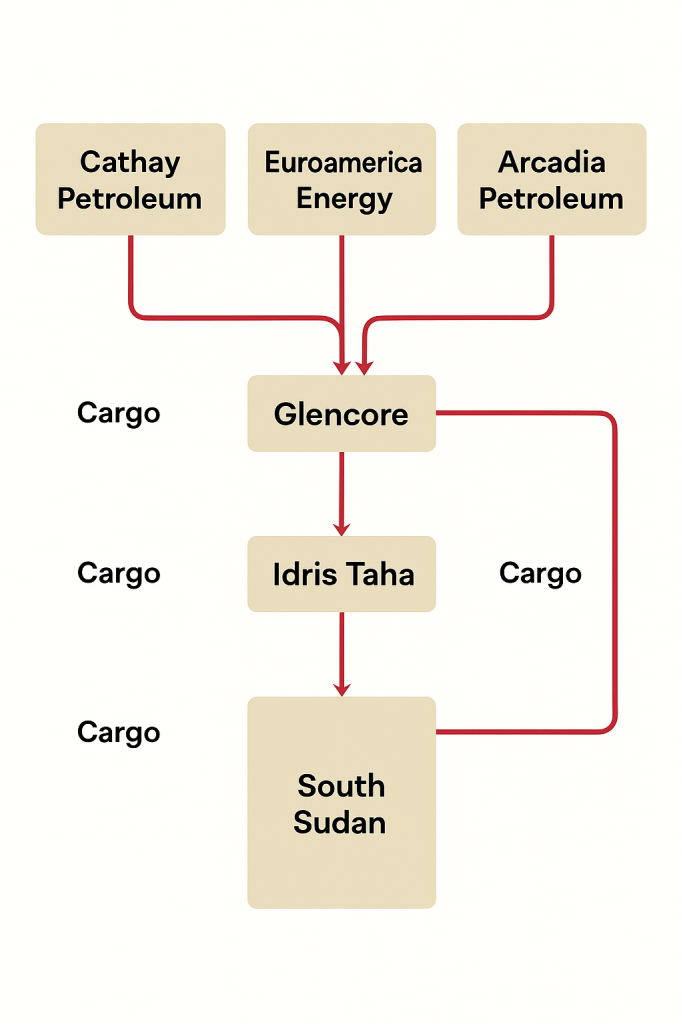

Investigations show that Cathay Petroleum inherited personnel and operational continuity from Arcadia Petroleum, a London-based trading firm active in the region. Key traders formerly employed by Arcadia and later by Glencore — a company publicly implicated in bribery schemes in South Sudan — now operate within Cathay, providing the company with direct access to longstanding networks. This lineage, described as the Arcadia-Glencore-Cathay continuum, has been reinforced through intermediaries like Idris Taha, a Sudanese-born businessman holding British and German passports, who plays a central role in managing Euroamerica Energy.

Euroamerica Energy currently controls over 80 percent of crude cargoes exported from South Sudan in recent months, operating with complete opacity and no prepayments. The network relies heavily on offshore and international channels, including Dubai, Turkey, and the United Kingdom, to move funds and cargoes. Idris Taha’s son Mahmoud regularly meets with local political figures, including former Vice President Benjamin Bol Mel, to facilitate operations.

The South Sudanese oil system itself appears structurally vulnerable to exploitation. Overbilling is rampant, with oil service companies connected to Bol Mel, Taha, and Cornelis Nicolaas Abraham Loos charging up to three times standard rates, fully reimbursed under the country’s cost oil framework. Examples include wells billed at USD 100 million despite costs of only USD 20 million. Combined with cargo diversion and underpricing, these practices have siphoned hundreds of millions of dollars from public coffers.

The trading system is further complicated by a cascade of hidden intermediaries. First-tier entities like Euroamerica Energy, Wellbred, and EPDSA receive crude directly from the producer before reselling to a second layer, which includes Cathay Petroleum and BGN. Only at the final stage does the crude reach refiners and international buyers, who often remain unaware of the complex and artificial chain. Sources indicate that global majors such as ExxonMobil are forced to purchase through these opaque channels, with traceability deliberately diluted.

Experts warn that the convergence of overbilling, cargo diversion, shell entities, and political facilitation has created an entrenched predatory ecosystem. The sudden surge of Cathay Petroleum, the near-total dominance of Euroamerica Energy, and the reliance on family networks and offshore banking illustrate a system designed to evade oversight. Observers say the combination of structural vulnerabilities and high-risk intermediaries poses serious legal, financial, and reputational risks for any institution engaged in South Sudanese oil.

The case raises urgent questions for policymakers, regulators, and international buyers about the sustainability and transparency of South Sudan’s oil sector. The systemic insertion of intermediaries, the reactivation of historical high-risk networks, and the lack of independent verification suggest that hundreds of millions of dollars are being diverted from the state while the country continues to rely on oil revenues to fund public services.

If you want, I can also produce a visual network diagram showing Cathay, Euroamerica, Arcadia, Glencore, and the intermediaries and their cargo flows. This would make the complex scheme immediately clear to readers.

Do you want me to create that diagram?

There's no story that cannot be told. We cover the stories that others don't want to be told, we bring you all the news you need. If you have tips, exposes or any story you need to be told bluntly and all queries write to us [email protected] also find us on Telegram