In July President Uhuru Kenyatta launched a task force chaired by investment banker John Ngumi to review the expensive Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) entered into between various Independent Power Producers (IPPs) and Kenya Power, including Ormat’s for the Olkaria complex.

The directive followed recent losses at Kenya Power and expensive electricity bills to consumers have shifted focus to lucrative deals signed between Kenya Power and IPPs. Kenya Power has 12 IPPs, namely Iberafrica Power, Tsavo Power, Thika Power, BioJuole Kenya Limited, Mumias-Cogeneration, OrPower 4., abai Power, Imenti Tea Factory Hydro, Gikira Hydro, Triumph Power, Gulf Power, and Regen-Terem Hydro.

In 2018, Kenya Govt seriously considered terminating the contract with expensive Independent Power Producers (IPP) who mostly use fossil fuel or thermal means to produce electricity. The expensive deals denominated in dollars were signed when Kenya was facing electricity shortages due to reliance on hydroelectric power and have continued to be renewed even when the country established cheaper wind and geothermal power.

The nature of the deals has made the IPPs a significant source of Kenya Power’s revenues despite the utility firm raking in losses.

US energy firm Ormat Technologies is in a parliamentary investigation into private contractor deals with Kenya Power.In regulatory filings with the US Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), Ormat said Kenyan MPs have asked for details of their operations at Olkaria and agreements with the monopoly electricity supplier.

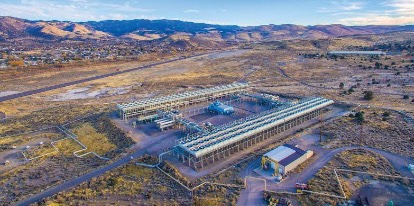

Ormat operates within the Olkaria III complex where it outputs 150 megawatt of geothermal power. The firm disclosed that in the six months to June its international electricity operations accounted for 34 percent of its revenues with a substantial portion coming from Kenya, suggesting that Kenya is the firm’s most lucrative single market.

In the filing, Ormat said even though it had production disruptions at the Olkaria complex, shareholder interest was protected by the Kenya Power agreements from variation in electricity generation due to fixed payments. The impact of the curtailments is limited as the structure of the PPA secures the vast majority of the company’s revenues with fixed capacity payments unrelated to the electricity actually generated,” the firm said.

Kenya is crucial to Ormat’s financial well-being. In its 2020 annual report, Ormat disclosed that its international electricity operations accounted for 28% of revenue and 70% of net income, with a “substantial portion” coming from Kenya, which “contributed disproportionately to our gross profit and net income”.

Kenya’s lopsided contribution is despite Kenya only representing 16% of its generating capacity, suggesting that Kenya is Ormat’s most lucrative single market.

This begs the question: how did such an advantageous deal for Ormat come about?

A Politically-Connected “Tycoon”, Joseph Manga Mugwe “Opened the Door” for Ormat and Made a Personal Appeal to Kenya’s Notoriously Corrupt President, Daniel Arap Moi

When Ormat arrived, Kenya was on the verge of a drought-fueled energy shortage and ruled by a rampantly corrupt government led by President Daniel Arap Moi that, during 24 years in power, robbed from state coffers and took billions in kickbacks from private enterprise.

Against that backdrop Ormat was able to negotiate terms so favorable that today it receives energy tariffs almost 40 percent higher than other geothermal contracts. Through an interview with the prior landowners of part of Ormat’s Kenya operation that the company established operations in Kenya with the help of a self-described consultant with impeccable political connections, Joseph Manga Mugwe. Described as a “tycoon”, Mugwe in an interview said that then-president Daniel Arap Moi – deemed one of Kenya’s most corrupt post-colonial rulers – personally gave approval for Ormat’s operations in Kenya.

More confusing is the contradicting information on Mugwe’s firm portfolio of directors that one person ‘Manga Mugwe’ is profiled twice using the same name under different photos which only goes to show how the intention is to throw investors off the cliff as to who the real Mugwe is. Dishonesty at large.

Mugwe Acknowledged in an Interview With Hindenburg That He Used His Political Clout to Facilitate Ormat’s Entire Operation in Kenya

He readily explained that his role had been much larger, claiming to have facilitated Ormat’s entire operation in Kenya.

“Orpower (Ormat) came to me and I helped them get a license yes, yes, yes. I’m the one who helped them through the door in Kenya.”

This unofficial consultancy role seems to have been a clear conflict of interest. At the same time that Manga Mugwe was facilitating Ormat’s entry to Kenya he was also a director of KenGen, the state power generation company that controlled geothermal resources at that time – including the resource it ceded to Ormat.

Despite this, he openly acknowledged that Ormat executives were referred to him by officials in the state electricity company KPLC – the company with which Ormat was about to sign a PPA and the sister company of Kengen — because of his political clout.

He admitted to regularly used to meet Ormat’s founders, Lucien and Dita Bronicki, when they came to Nairobi. He made a direct and personal appeal to then-president Daniel Arap Moi for Ormat to be given a contract in Kenya. To make way for geothermal development, nomadic Maasai herding communities were then forcibly displaced by internationally-funded projects from across the Olkaria geothermal field. Hardly the ESG angle that many investors believe they are getting when investing in Ormat.

Manga Mugwe.

Ormat’s Contractors in Kenya: Consistently Close Ties To The Empire of Former President Daniel Arap Moi, Looted More Than $1 Billion from Kenya

Detailed in a leaked report by international security firm Kroll, former Kenyan President Moi’s sons and business cronies helped run his racket via front companies and offshore bank accounts. It was amid this climate of rampant corruption that Ormat first arrived to do business with the Moi government.

Ormat’s Kenyan plant was developed in multiple phases spanning almost 20 years and three presidencies, eventually growing from 8 MW capacity to 150 MW. Ormat listed several contractors in a 2012 exhibit for a loan for its Kenyan Olkaria III project.

From this list, multiple companies run by close associates to Moi, including his son. Others were led by businessmen with close political and economic ties to the Mwai Kibaki Presidency (2002-2013), a former Moi minister who later moved into opposition. During Kibaki’s tenure, Ormat’s PPA was modified twice, allowing it to increase capacity.

The contractor list was not complete, but rather appeared to be a snapshot of a limited timeframe between late 2011 and mid-2012. Some of the contractors, however, were known to have worked with Ormat for many years.

Overall, it paints a picture of a network of private contractors tied to Kenyan political interests, facilitating payments to politically-connected individuals.

Uhuru’s son Jomo Kenyatta and Miss Ngina Kenyatta together with Mr Mugwe Manga (far right) on there first visit to Marrakech, Morocco. File photo.

Ormat Was Investigated in Kenya in 2017 After Whistleblowers Alleged The Company Had Overbilled Kenya’s State-Run Entity

The Standard published an article several months ago which have been removed that disclosed that Ormat was investigated in 2017 by the Kenyan Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) over corruption allegations.

The investigation was triggered when anonymous whistleblowers claimed Ormat’s Kenya plant had misrepresented its capacity and had forced its operators to report altered daily meter readings, among other allegations.

While the commission’s report ultimately failed to bring conclusive evidence of corruption, it found certain alarming issues. In one example, the EACC learned that the amount of power fed to the grid by Ormat’s plants was communicated verbally or through email to the National Control Center, instead of automatedly. The report identified this issue as potentially leading to “erroneous data for the invoice inputs”.

Two Former CEOs Of Ormat’s Key Kenyan Customer, Kenya Power, Were Arrested In 2018. More Than A Dozen Top Managers Were Also Arrested Or Accused Of Crimes.

Ormat’s sole customer for its 150MW capacity Olkaria III Complex in Kenya is a state-run entity Kenya Power and Lighting company. Just as with Ormat’s utility customer in Guatemala, Kenya Power has grappled with rampant corruption.

In July 2018, Kenya Power’s CEO, Ken Tarus, was arrested for “economic crimes” including “scandals involving bogus tenders and suppliers with the alleged theft of hundreds of millions of shillings by state officials from several government bodies.”

As part of the same USD $45 million corruption case, at least 9 other Kenya Power managers and former managers have been arrested, including former CEO Ben Chumo. This is the same Ben Chumo that oversaw Ormat’s approved 2014 power plant expansion, per Ormat’s SEC filings.

Later media reports in early 2020 speculated that “cartels at the company had swindled over Sh150 billion (USD ~$1.5 billion) from customers over a five year period” through overbilling. An ongoing investigation was expected to yield 15 more arrests, reports noted.

Multiple Other Key Signatories on Ormat’s Contracts in Kenya Were Later Charged With Corruption

Corruption at Kenya Power is not new. Samuel Gichuru was the longstanding head of Kenya Power (1984-2003) when Ormat signed its energy deal with the company in 1998. The contract was signed by the then Energy Minister Chris Okemu.

Gichuru was party to a letter affirming Ormat’s increase in capacity in 2000, per company filings. Both Gichuru and Okemu were later accused by prosecutors in Jersey of money laundering the proceeds of bribes and corruption through a front company based in the UK Channel Islands.

The pair dodged extradition but the Jersey Court confiscated more than $5 million in kickbacks which had been paid to Gichuru in just two years, 1999-2001. Recently, more assets were seized from the pair.

Court papers named 11 foreign companies, including Spanish, Finnish, British and Israeli entities, though Ormat does not appear. But Jersey judicial authorities confirmed in an email that these were sample charges and a sample list of companies. They said the full list of foreign companies who paid bribes to Gichuru was never submitted to the court.

Kenya Power Is Reportedly “Broke” And “Technically Insolvent”, Posing a Major Risk to Ormat’s Lucrative Arrangement in the Country

The extensive historical corruption at KPLC have exacted a painful price on the company and ultimately, Kenyan citizens. KPLC’s most recent financials note that Kenya Power has “remained in a negative working capital position for the third consecutive year” with current assets of KES 44 million versus current liabilities of KES 115 million. The financial audit notes that “strategic initiatives…undertaken to improve the financial results of the company…appear not to have yielded the intended results.”

“Broke” And “Technically Insolvent” Kenya Power Has Been Consistently Late Paying Ormat.

Kenya Power’s financial hardships are starting to show up in the utility’s apparent inability to pay Ormat on time. In Q1 2019, Ormat began reporting a late balance due from Kenya Power.

The late balance has been increasing significantly since it was first disclosed, as has the average number of days Kenya Power has been in arrears.

Ormat says that while Kenya Power is late on its bills, it is still expected to pay the balance. As a result, Ormat has apparently not set aside an allowance for credit losses pertaining to Kenya.

Financial volatility from Kenya could immediately translate to a material negative for Ormat’s balance sheet, as well as its ongoing profitability.

Evidence of corruption has now reduced Kenya’s willingness to continue to support Ormat’s lucrative contract in the country hence the presidential directive for investigation. We expect the blowback to these revelations to be severe, threatening Ormat’s contracts in its most lucrative markets.

Immediately prior to their work at Ormat, several senior Ormat executives and directors worked at Shikun & Binui, a leading Israeli construction company. Shikun & Binui were charged by Israeli prosecutors with bribing officials in what are now two of Ormat’s key markets, Kenya and Guatemala.

Ormat’s General Counsel & Chief Compliance Officer, along with an Ormat director, are under pre-indictment in Israel -a formal stage of prosecution just prior to indictment. Ormat has apparently chosen not to disclose that the two are currently in the midst of a criminal prosecution. Both still serve in senior oversight roles at Ormat.

Ormat CEO Doron Blachar’s immediate prior work experience was serving as CFO at Shikun & Binui. The CEO during Blachar’s entire tenure at Shikun & Binui was arrested in 2018 over the above-referenced bribery allegations. It is unclear whether Blachar faces eventual risk of indictment as well.

Multiple former Ormat employees and business partners have revealed how Ormat routes sales of energy assets in Guatemala through an undisclosed related party entity. Guatemalan corporate records corroborate these claims.

The entity shares an address with several Ormat subsidiaries and was set up by a former Ormat senior employee-turned “independent” consultant who answers directly to senior Ormat leadership, according to the former employees.

Official corporate records show that the same Guatemalan entity funneled energy rights to two senior government officials who were responsible for approving Ormat’s original deal in the country; the former head of the Mines & Energy Ministry and the former head of the state utility company.

Another Guatemalan Mines and Energy Minister, who was in office when Ormat was later awarded major improvements to its contract, was fired and charged with corruption by the United Nations-created anti-corruption commission. He is currently on the run with an outstanding international arrest warrant.

Ormat’s operations in Kenya contribute disproportionately to the company’s bottom line, generating an estimated ~41% of the company’s FY 2020 net income as stated earlier.

In Honduras, Ormat charges the state energy company roughly the same rate as end customers pay, virtually guaranteeing a loss for the state. These rates make no economic sense. The power agreement assumed by Ormat in Honduras was signed within days of other uneconomical agreements that were signed by the then head of the state utility, who is now under investigation for corruption relating to those agreements.

An opaque Panamanian entity with no public presence, formed the day after the Honduran coup, registered to unnamed nominee directors, was inserted into the deal.

Ormat’s Honduran plant operates in Copan, known as drug cartel territory. A Honduran congressman said “You can’t operate in Copan without paying the cartels, the gangs or corrupt politicians – and sometimes all three.”

Ormat’s contractor in Honduras was raided by authorities on suspicion of being a front company for drug cartels. Its owners are in jail awaiting trial. Ormat’s culture of corruption isn’t limited to international markets. In the U.S., Ormat settled DoJ fraud charges after whistleblowers alleged it made fraudulent misrepresentations in order to secure government clean energy loans.

Hindenburg linked Ormat employees to Shikun & Binui, an Israeli construction company. The report said the Israeli authorities had charged Shikun & Binui with bribing officials in Kenya and Guatemala.

Ormat’s CEO Doron Blachar had previously worked as CFO at Shikun & Binui. Hindenburg report cited documents appearing to show the company paid contractors in Kenya with links to “corrupt government officials”.

Hindenburg seemed to take particular umbrage at Ormat’s ESG credentials. The short seller noted that it had also published reports recently on other “ESG-oriented companies” such as Nikola and Loop Industries.

“We believe Ormat is another ESG imposter masking a different underlying issue: corruption.”

While Ormat has utility like aspects, the company is trading at expensive multiples. As Hindenburg noted, the market values Ormat at seven times sales and 63 times estimated 2021 earnings. Ormat was trading at $103.23 per share on February 24. As of March 2, it had fallen to $84.13.

Terminating the expensive Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) might help bring down the cost of power.

Kenya Insights allows guest blogging, if you want to be published on Kenya’s most authoritative and accurate blog, have an expose, news TIPS, story angles, human interest stories, drop us an email on [email protected] or via Telegram

There's no story that cannot be told. We cover the stories that others don't want to be told, we bring you all the news you need. If you have tips, exposes or any story you need to be told bluntly and all queries write to us [email protected] also find us on Telegram